Brother had meetings on our third day, so one of the employees of the family building was our driver for the day. Kingston refused to take on the challenge of the chaos that is Mumbai traffic even though he learned to drive in Mumbai (and we agreed that it was a wise decision). Without the retraints of Brother’s schedule, we had ample time today to indulge in the breakfast variety that our hotel offered at our leisure. Prior to our trip, Kingston had exposed us to the Indian breakfast selections of dosa and idli but I preferred sunny side up eggs on toast (which would be modified later when I got further exposure to the various Indian breads). I did experiment with the various Indian chutneys that were offered. My US experience with chutney was largely limited to a side of mango chutney with any spicy meat dish. In India, a chutney is a condiment made from almost any fruit, vegetable or spice with vinegar and sugar (the sweet/savory mix that Kingston loves). My breakfast favorites were tomato and mint, but I experimented with whatever the chef offered that day. At this point, I had not discovered my love for Indian coffee so I continued my European travel tradition of at least three cappuccinos every morning. I did at least finish off the meal with mango yogurt and a vanilla lassi (when it was available). So we really did not need a lunch but Kingston (who ate at his home) would have other plans for us. Lena needed to concentrate on the difficult task of finding housing for her graduate program in Europe while Dawn and I wanted to see Mumbai’s famous history museum. Lena does not list history museums very high on her traveling preferences, so we parted company for the day.

Originally named the Prince of Wales Museum, it was renamed in 1998 after Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, the founder of the Maratha Empire.

We navigated the chaos that is the traffic of Mumbai to return to the heart of Old Bombay, very near our first stop in India, the Gateway of India. The museum documents the history of India from prehistoric to modern times but plays its own role in that history. Originally named the Prince of Wales Museum of Western India, it was founded to commemorate the Prince’s royal tour of India from November 1905 to March 1906. In 1998 (two years after Bombay was renamed Mumbai), the museum was renamed the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaja Vastu Sangrahalaya or CSMVS as an acronym. The city historian protested “Since we are doing away with colonial names, Prince of Wales had to go. But a simple name like the Museum of Western India would have better defined the architecture and scope of the musem.” Shivaji was the founder of the Maratha Empire, a Hindu dynasty that contributed to the decline of the Mughal Empire (Muslim rulers from north of the Hindu Kush mountains). Although he was famous as a Hindu military ruler, he died in 1680. The state where Mumbai is located is Maharashtra (the local language is also Maharashtra), so there may also be some local cooking to honor the Maratha Empire achievements. A better understanding of Hindu/Mughal (Muslim) dynamics may better explain the decision to name the museum after Shivaji (and explain the number of statutes in his honor).

The Prince and Princess of Wales (later to be King George V and Queen Mary) had embarked on a tour of India in response to the rise of the influence of the Indian Independence Movement, founded in 1885 (the first modern nationalist movement in the British Empire). The hope was that their royal visit (the first trip to India by members of the British Royal family) would inspire loyalty to the crown among the Indian populace and leadership. The visit would, according to many historians, profoundly affect both royals but did little to deflect Indians from their pursuit of independence. The King lamented the second class treatment of Indians (including the royal Maharajas), but his views were not shared by the British Indian administrations. Queen Mary would refer to “lovely India, beautiful India.” They would return to India for a five-week tour from December 1911 to January 1912, the first time 300 years that a reigning British monarch would set foot on Indian soil.

On the news in 1904 that the Prince was planning a visit, some of the leading British citizens of Bombay decided a museum should be created to commemorate the visit. On August 14,1905, the committee formed to bring the idea to reality wrote: “The museum building embodies the pomp and height at which the British raj was moving ahead with their ambitious plans, in building the great metropolis Bombay.” The Prince of Wales laid the foundation stone on November 11, 1905, and it was announced that the museum would formally be named the “Prince of Wales Museum of Western India.” Following an open design competition, British architect George Wittet was commissioned to design the museum building in 1909. Wittet had already worked on the design of the General Post Office and in 1911 would design the nearby landmark, the Gateway of India. His design is a blend of Indian, Mughal and British engineering styles in stone and lattice work. Most of the building was completed in 1915, but it was used as a Children’s Welfare Centre and a Military Hospital during the First World War. The building was returned to the committee in 1920 and formally opened to the public in January 1922.

The CSMVS houses almost 50,000 of some excellent artifacts of the rich and diverse history of India but no pictures are permitted in the galleries.

The Leopold Cafe & Stores

After our long morning in the museum, Kingston decided it was time for lunch. His selection was a popular site in the Old Bombay neighborhood, the Leopold Cafe. It was founded in 1871 by Iranis, which is the term used for Zoroastrians who arrived in then Bombay India in the late 1800s. At that time, religious persecution of Zoroastrians in Iran was widespread. In India, there was already a fairly large population of Persian Zoroastrians (known as Parsis) who had migrated to Iran in the 700’s CE after the Arab Muslim conquest of the Persian Empire. They were trying to escape persecution by their new Muslim rulers. Zoroastrianism was the majority religion in Iran at the time of the Muslim conquest. Those Persians settled mainly in Gujarat, the state just east of Mumbai’s state of Maharashtra. There are about 70,000 Zoroastrians in India today. Because the tradition of marriage within the religion is so strong, even Parsis are still largely genetically Persian despite living in India for over 500 years. While Parsis now speak a variety of Gujarati, some Iranis still speak Persian and Dari (the variety of Persian spoken in Afghanistan). Iranis are generally seen as a subset of the wider Zoroastrian community. Upon arriving in India, many Iranis opened restaurants now often termed “Irani cafes.” Cafe Leopold was, for some reason, named after the King of Belgium (not sure if they meant Leopold I or II). It first started out as a wholesale cooking oil store and over the years has variously been a restaurant, store and pharmacy (hence the name “Leopold Cafe & Stores”).

It has been a popular hangout particularly for foreign tourists due to its proximity to the Gateway to India and other Old Bombay tourist attractions. Its logo also uses a Persian lion figure to indicate its Zoroastrian affiliation. While it is always difficult to understand what motivates a terrorist (the Zoroastrian logo, the foreign tourists, both or something else) on November 26, 2008, Muslim terrorists linked to Pakistan attacked the Cafe at 9:30am. It was their first target about an hour after they landed in Mumbai. Several of the terrorists walked up to the Cafe and sprayed it with machine gun fire from the street, killing ten people and injuring many others. They then walked to the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, where they began their four day siege that captured the world’s attention. The Cafe reopened four days after the attack but police asked them to close again after a very large crowd gathered in defiance of the attempts by the terrorists to intimidate Mumbai. Unlike the Hotel (which repaired all its damage), the Cafe has preserved the bullet holes as a memorial to those who died and were injured that day. And the food was quite good.

Since we had been to a Zoroastrian restaurant, Kingston then explained the 54 acre park we had seen on our first day. It was slightly visible from the hanging gardens on Malabar Hill. At least since 900 CE, Zoroastrians have used towers in their funerary practices. Known as Towers of Silence, the bodies of deceased Parsis are taken to the Towers of Silence where the corpses are eaten by the city’s vultures. The religious consideration for this practice is that earth, fire, and water are considered sacred elements which should not be defiled by a corpse, which is considered “unclean.” Therefore, burial and cremation have always been prohibited in Parsi culture. Herodotus, the ancient Greek historian, observed the custom of Iranians exposing corpses to the elements as early as 500 BCE. Mumbai’s Malabar Hill park has five Towers. Only a special class of pallbearers are allowed in the Towers. Unfortunately, Mumbai’s population of vultures has been decimated by disease, poisoning and climate change. So the Zoroastrians have needed to find some solutions to speed up the decomposition process, including using solar concentrators (which only work in clear weather).

The Jewel House

After lunch, we were dropped off at the house where Mahatma Gandhi mostly lived (when not in prison) in Mumbai (then Bombay) from 1917 to1934. Gandi had begun his struggles for Indian rights in South Africa in 1893 as a lawyer. Twenty years later he returned to England (where he had obtained his law degree from University College in London) for treatment of a severe bout of pleurisy (a lung inflammation). His doctors advised him to return to India to escape the dreadfully wet English winter. So a friend offered him the modest mansion (known in Hindi as the “Jewel House”) in the exclusive Gamdevi precinct (adjacent to Malabar Hill). Bombay was then a major center for the developing Indian independence movement. It was in this house that Gandi began his use of the charkha (one of the oldest forms of a spinning wheel) to promote Indian self-sufficiency and to protest the English policy of importing cheap English-produced clothing made of Indian cotton. The first Indian flag would feature a charkha in its center. By 1920, after the British Parliament suspended the rights of Indian political prisoners to trials, he launched the Non-Cooperation Movement to persuade Indians to resist the British administration. This Movement was the beginning of Indian political awakening and was correctly perceived as a threat by the British Administration. Gandi encouraged Indians to make their own clothes and boycott British goods. This non-violent movement was officially ended by Gandi in February 1922 after British troops fired upon a group of about 2,000 non-violent protestors, killing 3 and wounding many others (shades of the Boston Massacre). The mob retaliated by burning a police station with the officers inside. Gandi, disappointed by the violence, felt the Movement was being compromised and called for it to end. Despite his call to end the Movement, the British authorities arrested him and imprisoned him for six years for publishing “seditious materials.” Several years after his release, in 1930, Gandi, despite resistance from the Indian National Congress, decided to promote non-violent resistance (“Satyagraha”) to the British salt tax and monopoly on salt sales. Gandi led a 24 day march to the sea. The original 78 marchers represented almost every region, caste, creed and religion in India. They were called the White Flowing River because they wore white Khadis (a hand woven cloth shirt). Upon arriving at the Arabian Sea, Gandi (along with the now thousands who joined the March along its path) made his own salt by evaporating sea water in violation of the salt monopoly. For the British, the salt tax represented over 8% of British Raj revenues. However, the tax was particularly hard on the poorest Indians (“a necessity of life” along with air and water, according to Gandi). His act (not unlike the Boston Tea Party) sparked large scale acts of Indian civil disobedience. It also attracted international attention for the novel use of non-violent resistance. So, of course, the British response was to again arrest Gandi. And the British authorities tried to end the resistance by attacking the non-violent protestors with steel tipped sticks in full view of the international press. Press reports of the violent British assault on non-violent protestors were read into the official record of the US Senate. Newsreels of the events were seen by millions around the world. The tremendous international outrage and the continuing Indian resistance finally convinced British authorities that their Raj depended on the consent of Indians. Lord Irwin, the Viceroy of India, called for Gandi to be released from prison to hold talks on a compromise. In eight meetings over 24 hours, a compromise was reached calling for Britain to end the salt tax and provide a vague “dominion status” to India at an unspecified time in the future. Future Prime Minister Winston Churchill called the agreement “a nauseating and humiliating spectacle.” My Indian son-in-law has a very different view of Winston than the one I was exposed to as a World War II ally. The misdeeds of trying to save an Empire necessitate an honest reevaluation of the British Aristocracy in World history (as opposed to Western history). Although the Gandi-Irwin Pact ended Britain’s oppressive salt tax and monopoly, Indian attitudes against the Raj and for independence had been permanently altered. It appears the British had forgotten a similar experience with a tax on tea that cost Britain part of their North American Empire (I guess Britain just can’t learn lessons from their own history). This one cost them their Indian Empire just 90 years after the bloody “Indian Mutiny” that created the Raj. (More on that history when we get to New Delhi.) The Jewel House is now a museum that recounts this history.

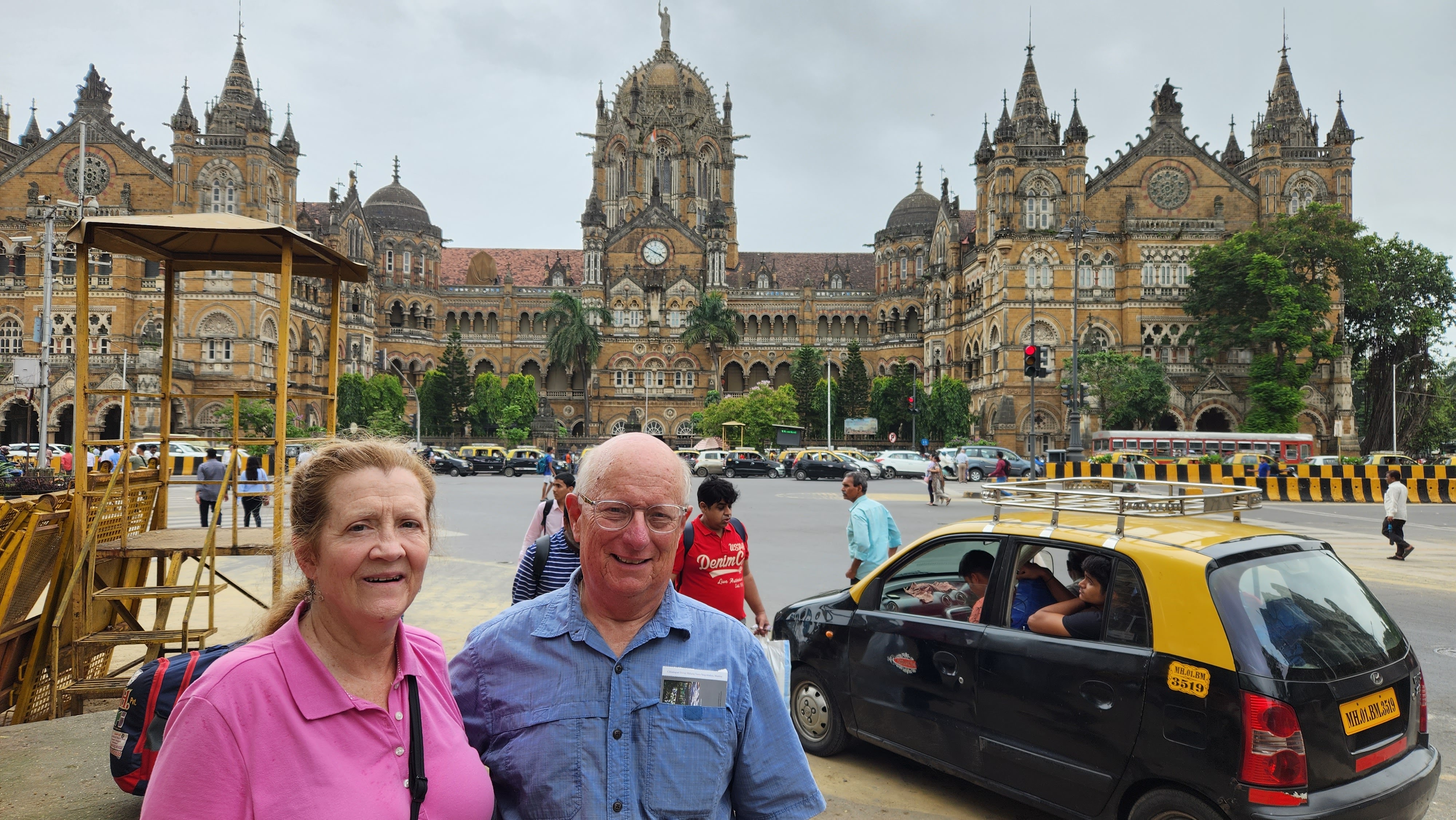

Main Mumbai rail station

Before we headed back to the apartment, Kingston decided that we should end our last day in Mumbai by experiencing the chaos of the Mumbai rail system (since we were already veterans of the chaos of the road system) by walking through the British era historic central railroad station at rush hour. Luckily for us, we were veterans of both the NY subway system at rush hour and the DC metro in a snow storm, so we were not caught totally unprepared. It was intense but not undoable and we emerged on the other side of the railroad station within 10 minutes where it took another 15 minutes to find the van driver (because traffic was worse). And we headed back to the apartment for another Indian dinner with the family.

Leave a comment