In an era marked by geopolitical fragmentation and open challenges to international norms, the relevance of international law is often questioned. Yet it is precisely under such conditions that international law is most significant. To that end, understanding the institutions that interpret and articulate international law—particularly in moments of strain—is essential. One such institution is the United Nations International Law Commission (ILC), which occupies a unique position in the international legal order.

This post is the third in a multi-part series connected to my work as an adjunct professor at American University, Washington College of Law, where I am teaching an upper-level practicum on the ILC. The aim of this series is to make the institutional role, working methods, and legal significance of the ILC more accessible to readers beyond the classroom.

As always, if there’s something you’d like to see added, clarified, or explored further, I’m happy to hear from you!

Introduction

After establishing the historical context and mandate of the International Law Commission (ILC) in the series’ first two posts, the next step is to establish the Commission’s structure.

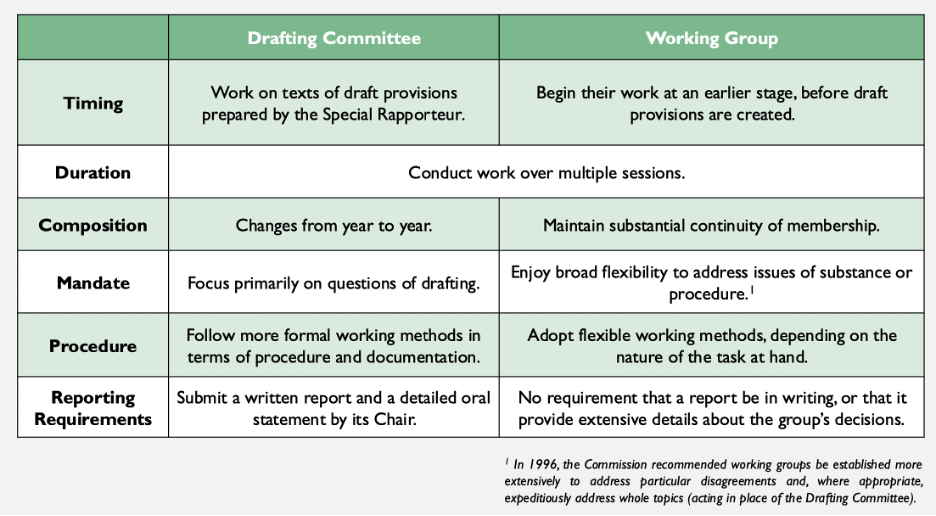

The Commission’s structure reveals a carefully calibrated institutional ecosystem. In regard to substance, the Commission’s Plenary Meetings establish direction and legitimacy, the Drafting Committees refine substance and language, and the Working Groups fill the remaining gaps. In regard to procedure, the Bureau, Enlarged Bureau, and Planning Group address the Commission’s overarching issues related to its long-term programme of work and methods of work. Commission Members also may run for election for six special positions: Chair, First and Second Vice-Chair, Chair of the Drafting Committee, and the Session’s Rapporteur for each year’s session; and a Special Rapporteur for each topic on the Commission’s agenda. Together, these meeting bodies and special positions form a cohesive institutional system that enables the Commission to produce rigorous, authoritative outputs that command respect within the international legal community.

Meeting Type: Plenary Meetings

The plenary is the central forum of the Commission. It is where all members meet to consider the reports created by Special Rapporteurs, working groups, study groups, the Drafting Committee, the Planning Group, and any other topic that requires consideration by the Commission as a whole. Members in plenary also decide whether to refer proposed draft provisions to the Drafting Committee, adopt provisional or final draft provisions and commentaries, consider and adopt the annual report to the General Assembly, and decide substantive and procedural issues (or announce any decisions that were reached in private or informal meetings[1]).

During most plenary sessions, Members give speeches to the Commission as a whole (which are called “interventions” or “commentaries”). For anyone who has done Model United Nations before, the structure of these speeches is almost identical to formal debate: Members add their name to a speakers list for the day, pre-draft their speech (which is submitted to official translators who are available for each official UN language and circulated to the other Members beforehand)[2], and speak for a specific amount of time determined by the entire Commission at the beginning of that year’s session (generally 15-minutes).

These speeches are used to comment on whatever is on the agenda for that particular meeting, which is normally a specific topic (e.g., immunity of state officials, sea level rise, general principles of law, etc.). When the Special Rapporteur of the specific topic has produced a report on said topic for that year’s Commission session, the comments will typically focus on discussing that report.

However, importantly, the primary function of speeches during plenary meetings is not line-by-line drafting, but general discussion. Through this general structured debate, members articulate overarching approaches to a topic, identify points of consensus or contention, and provide guidance to subsidiary bodies and the relevant Special Rapporteur.

As for transparency, plenary meetings are generally public[3] and the Commission’s annual report contains a summary of the plenary debate on each topic.[4] By monitoring these sources, States and observers are therefore able to follow the evolution of the Commission’s work. When the Commission’s work results in a treaty adopted by States, these records also constitute part of the treaty’s travaux préparatoires (aka the official record of a negotiation, which can be used to help interpret the treaty).

Interestingly, since 1997, the Commission has also employed “mini-debates”: short, thematic debates or exchanges of views in plenary on particular issues or questions raised during the consideration of a topic to facilitate a more focused discussion. However, the Commission does not utilize this power often.[5]

Meeting Type: Drafting Committees

The next meeting type, Drafting Committees, pick up where Plenary Meetings leave off. Drafting Committees are responsible for transforming the plenary discussion into precise legal language. For anyone who has done Model United Nations before, this type of meeting resembles a moderated caucus: there are no pre-prepared remarks, anyone may add their name to the agenda, and the Chair cycles through the speakers list until no one is left to speak (at which time the meeting will be adjourned).

In the Commission’s first three sessions, it set up separate committees to deal with specific topics or questions. However, in 1952, the Commission began using standing Drafting Committees, acting under a continuous chair, with the Commission’s session Rapporteur participating ex officio in each topic’s Drafting Committee.

Membership in the Drafting Committees varies by topic and session, and the number of Members participating have progressively increased with the increase in the Commission’s size. Careful attention is also paid to whether the Drafting Committees’ membership equitably represents the principle legal systems and UN working languages.

Picking up from the Plenary discussion, the Drafting Committee is responsible for line-by-line drafting, with the goal of harmonizing the various member’s viewpoints and finding generally acceptable solutions to difficult issues. However, if an issue proves too difficult to resolve in Drafting Committee, it may instead be transferred to a more informal discussion setting (such as a working group).

One of the most distinct features of the Drafting Committee’s work is its multilingual drafting. When discussing language, Members will consider the meaning of the text in the main drafting language (which is generally English) as well as the other UN working languages (Spanish, French, Arabic, Russian, and Chinese). This discussion will often uncover questions of substance, adding an additional layer of responsibility to the Drafting Committee’s work. To address linguistic issues, the Commission may also choose to adopt multiple versions of the same provisions in two or more authoritative languages. Additionally, when the Drafting Committee completes its work on a set of draft provisions, Members from the various linguistic groups may meet separately to ensure their respective linguistic versions align with the adopted text.

Once their work is completed, the Drafting Committee will present their proposals to the Commission, which generally adopts them by consensus (aka without taking a person-by-person vote).[6] That said, even after adoption, the Drafting Committee’s texts may still be amended.

As for transparency, unlike plenary meetings, the Drafting Committee’s meetings are closed to the public and their discussions are not reproduced in the Commission’s summary records. Instead, the Chair of the Drafting Committee delivers a public report during the Commission’s plenary session that summarizes the Committee’s decisions and explains drafting choices.

Meeting Type: Working Groups

Unlike the other two general meeting types, Working Groups are designed to provide the Commission with institutional flexibility. Established on an ad hoc basis by the Commission or by the Planning Group, Working Groups may address a broad range of topics. The establishing institution also provides their specific mandate (including, where appropriate, defining the parameters of any study or review to be conducted and making any necessary decisions on their work product). Dependent upon the needs of the specific topic, membership in Working Groups may be limited or open-ended.

The timing for when a Working Group is established also varies. Historically, the Commission has established Working Groups for new topics, before appointing a Special Rapporteur, with the goal of undertaking preliminary work or defining the scope and direction of the work. It has also created Working Groups after appointing a Special Rapporteur to consider specific issues, determine the direction of future work on a particular topic, or consider proposed commentaries and draft provisions. Occasionally, Working Groups may also be established to handle a topic as a whole due to the urgency of the issue or when the Special Rapporteur leaves the Commission.

As mentioned earlier, a Working Group may be established to prepare revised versions of a draft article (or guidance regarding the formulation of a draft article) that is later referred to the Drafting Committee. It may also be used to examine proposals for draft commentaries or consider the feasibility of work on a certain topic (or the best way forward for the Commission to address said topic). The Working Group’s final outcome is typically a report that is either (a) presented orally by the Working Group’s Chair to the Commission in plenary or (b) issued in written form as a document annexed to the Commission’s report.

Interestingly, when the Working Group’s mandate includes drafting a final product, the product may be submitted directly to the Commission in plenary—bypassing the Drafting Committee. This flexibility allows the Commission to avoid duplication or mistakes, which could be made if Drafting Committee members were not equally present for the discussions in the Working Group. However, the Drafting Committee may be used to conduct a final review, with the limited mandate of evaluating the adequacy and consistency of language (rather than content) of the Working Group’s final product.

Starting in 2002, the Commission created a new type of Working Group: “Study Groups”. The most recent example is the study group created to address the topic “Sea-level rise in relation to international law”, which completed its work in 2025. This type of Working Group is intended for use only in exceptional circumstances in order to consider particularly unique topics. Their purpose is to achieve concrete outcomes, in accordance with the mandate of the Commission and within a reasonable time. Thus far, the Commission has not appointed Special Rapporteurs for study groups, instead using Chairs (or Co-Chairs).

Drafting Committees and Working Groups: Compared and Contrasted

Special Meeting Groups: Bureau, Enlarged Bureau, and Planning Group

In addition to these general meeting types, there are three types of specialized meeting groups. These groups are typically used to manage the Commission’s workload and plan its future activities.

The first type—the Bureau—consists of the five Members elected to special positions (so called “Officers”) at that year’s session. It considers the Commission’s schedule of work and other organizational matters with respect to that year’s session.

The second type—the Enlarged Bureau—consists of the Officers elected at that year’s session, the former Chairs of the Commission who are still members, and the Special Rapporteurs. It considers general issues related to the Commission, its programme of work, and its methods of work.

Lastly, the third type—the Planning Group—performs a vital strategic function in that it establishes a “Working Group on the Long-Term Programme of Work”. This Working Group maintains the same Chair and membership during each of the Commission’s five-year terms, which is tasked with recommending topics to include in the Commission’s long-term programme of work. The Planning Group may also establish a Working Group to review and consider ways of improving the Commission’s methods of work (on the Commission’s own initiative or based on a request by the General Assembly).

Special Positions: Officers

To facilitate the procedural aspects of their work, each session of the ILC begins with the election of five officers from the Commission’s general Membership: a Chair, two Vice-Chairs, a Chair of the Drafting Committee, and a Session Rapporteur.

The Chair presides over meetings of the plenary, the Bureau, and the Enlarged Bureau, guiding both procedural flow and substantive debate.[7] The First and Second Vice-Chairs exercise the same powers when designated to act in the Chair’s place.[8]

The Chair of the Drafting Committee plays a particularly influential role. In addition to presiding over Drafting Committee meetings, the Chair recommends the committee’s membership for each topic and introduces the Drafting Committee’s report when it is considered in plenary session.

Lastly, the Session’s Rapporteur is responsible for drafting the Commission’s annual report to the General Assembly—the authoritative document that describes the Commission’s work and records the Commission’s conclusions.

Interestingly, in accordance with long-standing Commission practice, these officer positions rotate among Members from various regional groups—reinforcing the Commission’s commitment to geographic balance and representativeness.

Special Positions: Special Rapporteurs

Another specialized position that Members may undertake is the role of Special Rapporteur. Special Rapporteurs are the intellectual anchors of the Commission’s work. Although the Commission’s Statute formally envisages the appointment of Special Rapporteurs primarily for topics of progressive development,[9] in practice, the Commission appoints a Special Rapporteur at the beginning of its consideration for each topic—regardless of the topic’s potential classification as “codification” or “progressive development”.

Since 1949, there have been 69 Special Rapporteurs.[10] Once appointed, the Special Rapporteur retains their rule until the topic is complete, or they leave the Commission. Importantly, when a Rapporteur needs to be replaced, the Commission typically suspends work on the topic temporarily, reflecting the centrality of the Special Rapporteur’s role and the importance of continuity.

Special Rapporteur’s responsibilities are extensive. They prepare detailed reports on the topic that include detailed explanations of the state of the law (e.g., surveys of State practice, jurisprudence, and doctrine), explanations of previously expressed opinions by both Commission Members (in prior plenary sessions) and States (in State commentary submitted directly to the Commission and commentary presented during the UN General Assembly Sixth [Legal] Committee sessions), and proposed draft provisions.[11] These reports form the foundation for the Commission’s work. Special Rapporteurs also contribute to the Drafting Committee discussions, write commentaries explaining the legal basis and implications of proposed texts, and write any other necessary working documents for the Commission and/or Drafting Committee. They also help define the scope and direction of the Commission’s work in subsequent sessions.

In Plenary Meetings, the Special Rapporteur introduces the discussion of their topic (and any related report) with a special speech, responds to questions raised during the debate, and makes concluding remarks summarizing the main issues and trends at the end of the debate. Where appropriate, they also give a recommendation as to the referral of any draft provisions to the Drafting Committee or a Working Group.

As for Drafting Committees, the Special Rapporteur will serve as a member for their topic’s Committee. In this role, they are responsible for producing clear and complete draft provisions, explaining the rationale behind the draft provisions currently before the Drafting Committee, and reflecting the view of the Drafting Committee in revised draft provisions and related commentary.

Conclusion

Each of the elements described above—the general meeting types utilized by the Commission, the specialized meeting groups utilized by the Commission, and the special roles Commission members may undertake—form the foundational basis for the Commission’s work. Together, these elements enable the Commission to manage disagreement, preserve expertise, and produce legal texts that resonate far beyond the walls of the Palais des Nations. In a period of contested multilateralism and legal uncertainty, the Commission’s internal structure is not a procedural detail—it is a central condition of its enduring influence on international law.

[1] See Rule 61 of the Rules of Procedure of the General Assembly.

[2] Although the speeches are pre-drafted, Members may still deviate from them during their actual remarks.

[3] See Rule 60 of the Rules of Procedure of the General Assembly.

[4] One exception to this general rule occurs when the Commission adopts draft provisions and commentaries at the same session, in which case the draft provisions and commentaries are reprinted in the annual report instead.

[5] During the 2025 session discussion on Immunity of State Officials, the Commission members had a directed debate on whether draft article 7—describing the exceptions to immunity—should be sent to Drafting Committee. See A/CN.4/SR.3707 (pages 11 to 15).

[6] One exception to this rule occurred in 2017, where the Commission provisionally adopted draft article 7 for the topic ‘Immunity of State officials from foreign criminal jurisdiction’ by vote (rather than by consensus).

[7] See Rule 106 of the Rules of Procedure of the General Assembly.

[8] See Rule 105 of the Rules of Procedure of the General Assembly.

[9] ILC Statute, Article 16(a).

[10] Like Officers, the Commission’s Special Rapporteurs are traditionally distributed among the Members from the various regional groups.

[11] These reports are sent to the UN Secretariat’s Office of Legal Affairs, Codification Division, who coordinate the report’s review for grammar and translation, and circulate the reports to other Commission members.

Course Materials

References

International Law Commission, Structure of the Commission: https://legal.un.org/ilc/structure.shtml

International Law Commission, Special Rapporteurs: https://legal.un.org/ilc/guide/annex3.shtml

Leave a comment